State Sen. Josh Newman uses an ice cream truck to promote his campaign to retake the 29th Senate District on Saturday, Feb. 15, 2020 in Anaheim. Newman’s 2022 prospects could be challenging if draft maps of new political boundaries are finalized in December. (Photo by Michael Fernandez, Contributing Photographer)By BROOKE STAGGS | bstaggs@scng.com | Orange County RegisterPUBLISHED: November 11, 2021 at 6:59 p.m. | UPDATED: November 12, 2021 at 8:48 a.m.

Orange County might gain one more voice in Sacramento.

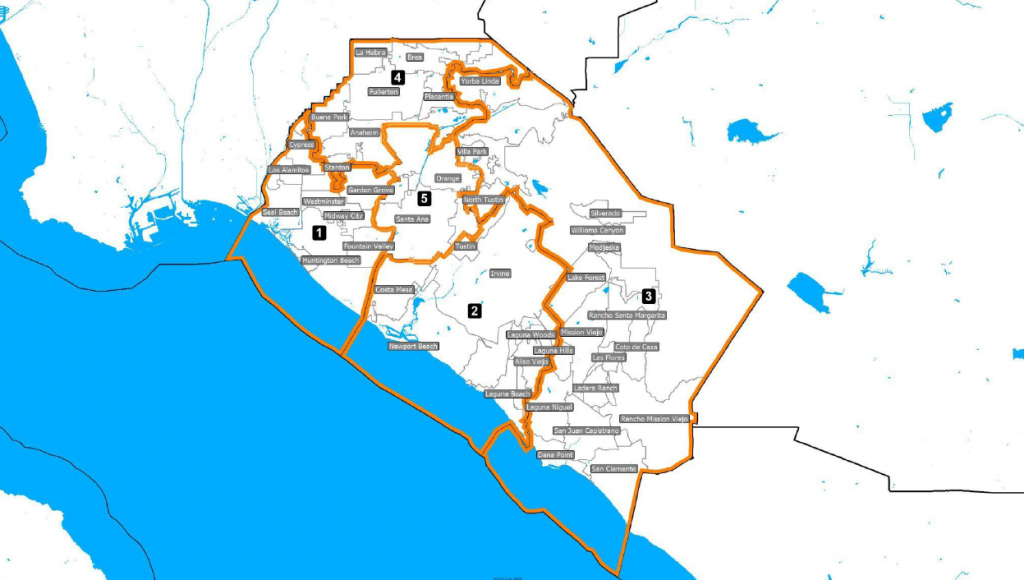

Draft maps of proposed new boundaries for state legislative districts, released late Wednesday by the California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, suggest taking the county from seven to eight Assembly districts to balance out population changes found in the 2020 Census.

But if the proposed boundaries stick, several local incumbents could face tough choices, with some representatives drawn out of their current districts or into new ones that figure to be less favorable to their 2022 re-election.

So, while these maps could change significantly before final maps are due Dec. 27, they’re already causing heartburn for some politicians and their consultants.

“This is the quandary for any legislator,” said State Sen. Josh Newman, D-Fullerton, whose district could get much more Republican if draft maps stick. He added that’s why redistricting is “not supposed to be up to us,” referring to elected officials.

The redrawing of political maps, known as redistricting, happens every 10 years, after the federal government publishes updated census information. This cycle, census data shows there needs to be about 988,000 people in each state Senate district and 494,000 people in each Assembly district.

In California, to avoid partisan gerrymandering and to make line drawing more transparent, the process has been handled since 2008 by a Citizens Redistricting Commission, which includes 14 volunteers who represent diverse political views and different parts of the state. They’ve been collecting public input and meeting for months, approving draft maps for all of California’s federal and state districts Wednesday night.

Those maps aren’t great news for Newman, who won the current SD-29 seat in 2016, was recalled in 2018, and won it back in 2020.

Newman’s district now leans solidly blue. But under the proposed boundaries, while he’d still live inside the district, he would lose much of his left-leaning city of Fullerton along with his portions of Anaheim and Los Angeles County. Meanwhile, he’d face voters from the solidly red eastern part of Orange County, from Anaheim Hills south to Mission Viejo.

Unlike House members, who only need to live in the same state where they run, state legislators are legally required to live in the district they represent. That might pose problems for State Sen. Bob Archuleta, D-Pico Rivera, if draft maps stick.

Archuleta represents a largely Los Angeles County district that now also includes a portion of Buena Park. The new lines would add a portion of La Habra, and it would not include Archuleta’s current neighborhood. That means he’d need to move into the newly drawn district or run against fellow Democratic State Sen. Susan Rubio in 2022.https://public.tableau.com/views/CASenateMaps/DraftMap?:embed=y&:display_count=yes&publish=yes&:toolbar=no&:showVizHome=no

Preliminary maps also draw State Sen. Pat Bates, R-Laguna Niguel, out of her district, which includes southern Orange County and northern San Diego County. But Bates is termed out next year and can’t run for re-election. She is considering a run for Secretary of State.

Both of the leading contenders for Bates’ seat — Republican Lisa Bartlett, a county supervisor from Dana Point, and Democrat Catherine Blakespear, mayor of Encinitas — appear to live in the district’s proposed new boundaries. But, as drawn, the new district could favor Blakespear, since it might include less of the GOP-leaning portion of O.C.

Prior to the release of the preliminary maps, some voters were concerned that the commission would split Little Saigon into two state Senate districts. Earlier, unofficial preliminary maps did show Little Saigon divided, with some parts staying in an area now represented by State Sen. Tom Umberg, D-Santa Ana, and the rest in new district that would include Garden Grove, Westminster and Seal Beach. Advocates of the Vietnamese community worried that the changes would weaken Little Saigon’s voice in Sacramento.

The latest draft keeps the heart of Little Saigon intact, but moves it to a potential new district now represented by State Sen. Dave Min, D-Irvine.

Orrin Evans, a political consultant who works on a number of Democratic campaigns in Orange County, said one concern about the new state Senate lines is that the county’s Asian American and Pacific Islander communities have been divided up between districts, mentioning Irvine and other key places. So Evans said he still sees lots of work to do to ensure the county’s AAPI communities have a strong voice in Sacramento.

On the Assembly side, the biggest hits might come to Assemblyman Stephen Choi, R-Irvine, and Assemblywoman Laurie Davies, R-Laguna Niguel.

Right now, Choi’s 68th District includes a slice of east Irvine, where he lives, and heavily red portions of southeast Orange County. But in draft maps, the new district would cover all of solidly blue Irvine plus portions of Tustin and Costa Mesa.

This week, prior to the maps being released, Irvine Vice Mayor Tammy Kim, a Democrat, filed to run for Assembly, setting up a potential battle with Choi.https://public.tableau.com/views/CAAssemblyMaps/DraftMap?:embed=y&:display_count=yes&publish=yes&:toolbar=no&:showVizHome=no

For Davies, her southern O.C. seat has been the the county’s most solidly Republican Assembly district. But the proposed new lines take in portions of blue-leaning northern San Diego County, which could attract new challengers from the left.

For many observers, one of the most perplexing proposals is the creation of a new Assembly district in southeast Orange County.

The cities of Rancho Santa Margarita and Mission Viejo, plus the canyon communities, are lumped into an Assembly district with Murrieta and Temecula, which sit on the other side of the Santa Ana Mountains in southwest Riverside County. While the Ortega Highway does connect the two areas, not much else seems to.

The maps also draw GOP incumbent Janet Nguyen into a coastal district with Democratic incumbent Cottie Petrie-Norris. And they take Little Saigon out of Nguyen’s district and create a new one centered around the Vietnamese community, sparking speculation that Nguyen might move if the proposal sticks.

Evans expects there will be significant changes to the maps before the Dec. 27 deadline, with public comment now open.

Residents can visit WeDrawTheLinesCA.org to learn more about the process and learn how to submit comments in writing or during upcoming hearings, which pick up Saturday, Nov. 13.