2021 Redistricting in Orange County

Redistricting provides a one-a-decade opportunity to shift power at all levels of government.

To ensure a community voice in the 2021 redistricting process, OCCET worked with 16 community-based organizations to establish the People’s Redistricting Alliance (PRA). Centering the lived experiences and needs of low-income communities of color and working families in Orange County, our multiracial coalition engaged in robust local organizing, research, mapping, and advocacy with the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (CCRC) and the Orange County Board of Supervisors.

After a year-long campaign, the PRA successfully advocated for changes to Congressional, State Senate, State Assembly, and Board of Supervisors districts that maximize opportunities for year-round organizing, policy advocacy, and narrative shifts and advance solutions that address the needs of the most marginalized communities in Orange County.

People’s Redistricting Alliance

- American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California

- AHRI Center

- Arab American Civic Council

- California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative

- Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights

- Council on American-Islamic Relations – Los Angeles

- Latino Health Access

- Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance

- Orange County Congregation Community Organization

- Orange County Communities Organized for Responsible Development

- Orange County Environmental Justice

- Orange County Voter Information Project

- Pacific Islander Health Partnership

- Resilience Orange County

- South Asian Network

- VietRISE

We welcome community organizations interested in getting involved in redistricting in Orange County! Please email us at redistricting@occivic.org

Redistricting is the process by which legislative district boundaries are re-drawn to reflect changes in population. Occurring every ten years after the census, it presents an opportunity to increase community voice in government and participation in the electoral process.

A community of interest is a contiguous population which shares common social and economic interests that should be included within a single district for purposes of its effective and fair representation.

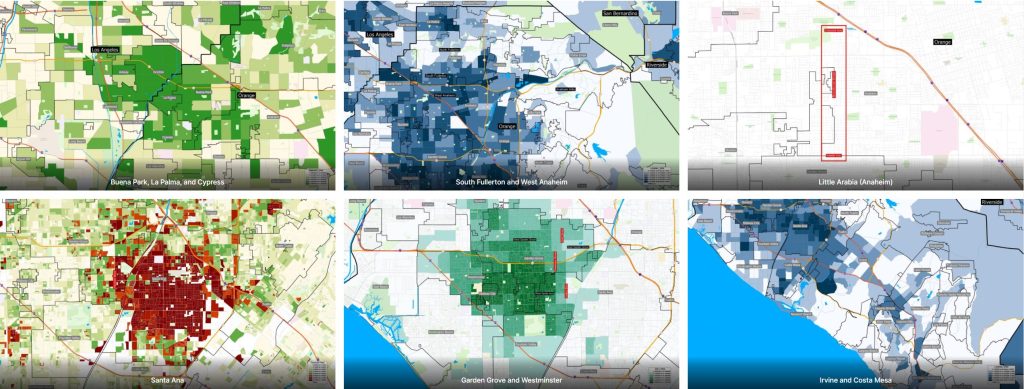

PRA member organizations met throughout 2021 to identify communities of interest and their alignment across cities in Orange County, and shared these with redistricting commissions and staff in public testimony.

The PRA submitted public maps for Congressional, Assembly, Senate and Orange County Board of Supervisors Districts to the California Citizens Redistricting Commission and Orange County Board of Supervisors during October of 2021. Our People’s Maps center federal Voting Rights Act compliance and communities of interest that reflect the needs of the county’s most impacted residents.

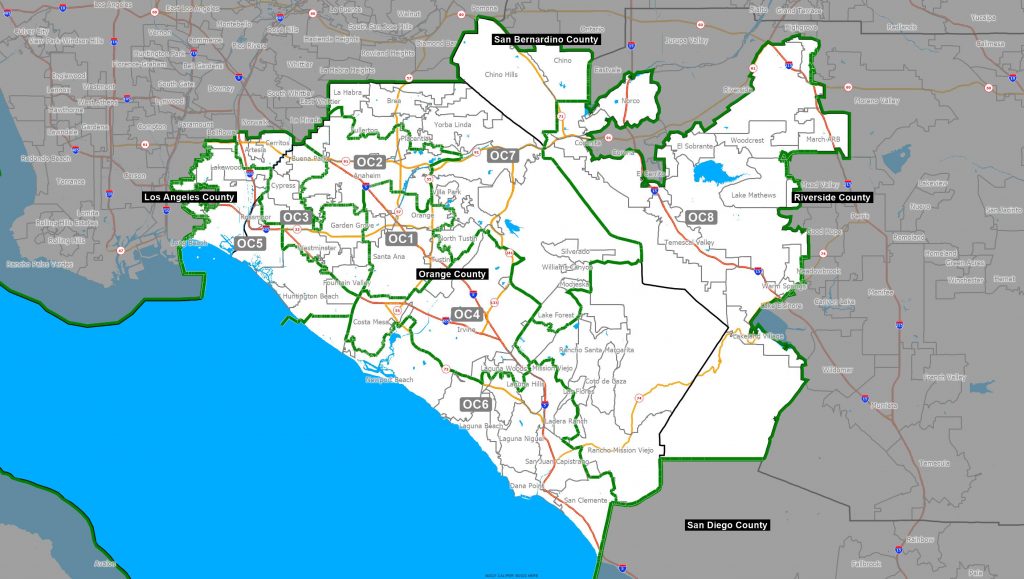

Through robust community engagement and organizing in the 2021 redistricting process, the People’s Redistricting Alliance successfully advocated for the creation of districts at all levels that center low-income communities of color and working families in Orange County. Over the next decade, these districts will create unprecedented opportunities to advance public policies and programs responsive to those most in need.

Get to know the new 2021 Legislative Districts in Orange County!